BORAX By Example - Part I

Let’s keep going with dreaming of a new rich Internet application using the BORAX architecture.

BORAX by Example

Just for review, the most common usage pattern of a rich internet application goes like this:

- Visitor GETs a main page of the application; visitor can’t access page and login form is shown

- Visitor POSTs credentials to server

- On failure: response contains login page (go to parent step)

- On success: response contains redirect to original page (go to next step)

- Visitor GETs page of application

- Broswer makes GETs and POSTs on behalf of visitor for information

- Responses most often contain media types

text/html,text/xml, orapplication/json - For

text/html, JavaScript plops new content into DOM - For

text/xml, JavaScript or browser applies stylesheet and plops transformed content into DOM - For

application/json, JavaScript using out-of-band information generates something to plop into the DOM or affect the current items in the DOM

- Responses most often contain media types

- Visitor interacts with application by GETting and POSTing to various URLs

- Visitor POSTs to logout URL (go to first step)

I’ll start at the top of the list, talk about the current state-of-the-art, then scrub it clean with some BORAX. First up:

Authentication - BOOM!

About twelve and one-half years ago, some folks from across the computer software world got together and wrote HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication. It describes two methods by which a user can authenticate with a server to prove their identity. The HTTP/1.1 standard references it and the two authentication methods “Basic” and “Digets” as the two options by which the ‘WWW-Authenticate’ header can work out-of-the-box. Unfortunately, while the RFC describes the method by which a browser authenticates, it does not address the situation where the browser or server wants to abandon the credentials.

That’s right: the standard does not provide for “logout.”

Oh, did I mention its age: 12-1/2 years old!? If I haven’t made a mistake, I think that describes the Paleolithic era of the Web.

In the interim, almost every single Web application has abandoned the excellent HTTP status code 401 Unauthorized and the “WWW-Authenticate” header because they can’t end a session, can’t intercept that ugly popup box the browser throws in front of the user, or can’t bother to have to set up the Web server to make the challenge.

It’s just so much easier to present a form and keep some token in the browser’s cookies. And it’s prettier. And, it’s an opportunity for branding. Until someone updates this or Kerberos becomes the Internet-wide standard for authentication, we need something better.

BORAX handles HTTP codes wisely

Enter BORAX. BORAX registers handlers for different HTTP status codes. That’s important because we want our server to tell us the disposition of the request which will provide us with much better processing for other types of requests as well as authentication.

With BORAX, any managed AJAX request that returns a 401 HTTP status code will use the registered ‘401 Unauthorized’ handler. The default handler probes for associated content for an authentication form or template in the following places:

- The body of the response if the “Content-Type” of the response equals

text/htmland the body has content - The body of the response if the “Content-Type” of the response equals

application/x.borax-linkbase - The body of the response if the “Content-Type” of the response equals

multipart/relatedand the “type” parameter equalsapplication/x.borax-renderable - In the response for a “Link” header with a relation of “authorization-template”

- In the

HEADof the currently loaded page for alinktag with a relation of “authorization-template”

Should all of these fail, BORAX will report an error to your application. If BORAX can find any of these, then it returns an object that your application can render into the DOM and a login form (assuming that content gets served by any of those methods) will appear in your browser!

Or, at least, it will….

I’ve just started this BORAX project. I haven’t completed the specifications

for the BORAX media types. As of the time that I’ve written this entry, I only

have the code to support the versions of interactions that return

text/html. However, since we only want to show a login form, then this

seems like a reasonable time to test the HTML rendering functionality.

That’s what I’ve got, right now. That’s what I’ll use.

Code

I usually hate abstracting “standard” libraries. I like to abide by “choose something and stick with it.” Otherwise, you end up with either leaky abstractions or least-common-denominator APIs. BORAX, though, acts more like a glue layer than a proper toolkit. That in addition to the religious fervor surrounding Web developers’ preferences has caused some design decisions with BORAX. The first example of that comes from the AJAX support in BORAX. BORAX doesn’t have any itself; it uses the one that you supply to it.

BORAX’s expectations of an AJAX provider does not align itself with any of the common libraries; you have to write an adapter, if I haven’t provided one with the distribution. Right now, that means jQuery. Later, it will mean whatever you or I write. I really like FOSS for that reason.

Get BORAX

You can do this two ways. You can download the packaged build or the entire

repository from GitHub from the

BORAX.js repository. If you want

to just look at the code, the BORAX repository has an example in the

“example” directory that you can run with npm start at the root of the

repository.

Right now, you can also point a Web server to that example directory since we

will work with only text/html, text/css, and

application/javascript.

Set up your application’s entry point

The entry point for a BORAX-enabled Web application probably consists of just

a basic HTML page. The page can instruct BORAX to transition to the first

state of the application by calling its start method with a URL. If you

invoke start without a URL, then BORAX will look for a link tag in

the current document with the “x.borax-start” relation type and use the

value of its href attribute.

For example, the index.html for the example application has the following content.

1 |

|

which renders

Line 6 of the start page indicates to BORAX that, on start, it should

transition state from the current state (nothing) to the start state

represented by the relative URL /dashboard.html.

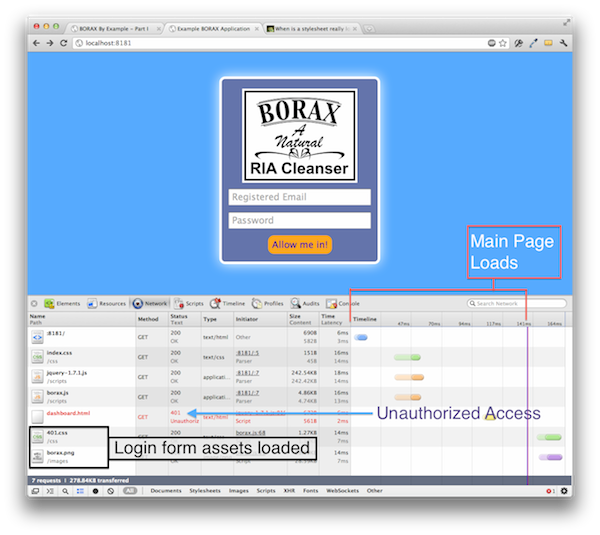

Unfortunately, the server protects that resource from unauthorized access. BORAX receives the 401 from the server. The communication between BORAX and the server went something like this.

1 | GET /dashboard.html HTTP/1.1 |

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

Connection:keep-alive

Content-Type:text/html

Transfer-Encoding:chunked

<link href=”css/401.css” rel=”stylesheet”>

<form id=”login-form” action=”.” method=”POST”>

<div>

<div class=”input-row”>

<div class=”image-holder”>

<img src=”images/borax.png” height=”157” width=”200” alt=”borax”>

</div>

</div>

<div class=”input-row”>

<input type=”email” name=”username” placeholder=”Registered Email”>

</div>

<div class=”input-row”>

<input type=”password” name=”password” placeholder=”Password”>

</div>

<div class=”input-actions”>

<button type=”submit”>Allow me in!</button>

</div>

</div>

</form>

BORAX parses that response so that renderers can intelligently deal with the

different aspects of how tags should appear in the actual page. In this case,

BORAX accesses the link tag and puts it into the head of the visible

document. Then, it puts the remainder, the form node, into the body of

the main document.

This gave you a glimpse of how BORAX handles different media types and response codes. More on BORAX will come in future posts as I complete more code. I think a friend and I will use it to create a new crapplication for the Web that allows people to get excuses to call into work sick, hurt, lost, or malaise-filled. It’s a funny idea. And, as the app grows, we will have the ability to create BORAX for a real-working application.